A short distance from the renowned, white dunes of Porto Pino, the lagoon of Porto Pino is located. A canal, which connects the lagoon and the sea, has been partially blocked by a barrier made by a cooperative of fishermen. Like the lagoon at Nora, young fish, which are born in the sea, seek safety and easy access to food in the lagoon. There, they grow up until their instincts make them return to the sea to spawn because the variable salinity and temperature of the lagoon will prevent the fertilised fish eggs from hatching. Before they can go back to the sea, they have to pass the canal where the fishermen have set up a barrier stretching across the whole width of the canal. Having a polygonal shape and being made of vertical bars which have been embedded in the sea bed, the barrier is easy to enter because it has an opening like a funnel, but difficult to exit. Besides, the mature fish try to cross the canal at high tide when there is a current from the sea to the lagoon. Then, the fish will only swim against the current and won’t return even though it would be possible to escape the barrier.

The movement of fish from the sea to the lagoon and vice versa has been known to man for millennia and their way of fishing is similar to that which has been practised since time immemorial.

Arriving at about 8 in the morning, we find Carlo and some of his colleagues inside the barrier, catching the fish by means of a hand-held net. One fisherman is standing still, holding one end of the net in the water, while another one is holding the net at the opposite end, walking slowly towards the first one, while gently contracting the space enclosed by the net. Finally, they meet and close the lower end of the net by means of a knot. Then, they carry it to an opening in the barrier where another fisherman is holding a bucket in which they empty the fish from the net. Finally, the fisherman on the outside brings the bucket with the fish back to the fishermen who are waiting for him on dry land.

Having lifted up the bucket, the fish is sorted. The most valuable fish, sea bass, is put in one bucket, while various species of sea bream, mullet, etc. are put in another one. Besides, fish which are too small are released into a large pond, connected to canal between the lagoon and the sea, but closed with a net such that they have to stay in the pond.

After the first selection, another selection is done in a large, quadratic and open box with perforated sides. The fish which were not sorted at the first selection are put in the box, water is poured over the fish, starting immediately to flow out of the holes in the side of the box. The fishermen sort the remaining fish quickly, putting them in styrofoam boxes and bringing them to a small shop where labels are put on each box. Locals are waiting for the fish to arrive at the shop and after having bought what they want, they return home with their “catch”.

Next morning, we are invited to join Raffaele and Samuele, father and son and both of them members of the cooperative, fishing in the lagoon near Porto Pino. Since we arrive early, Carlo willingly shows us how they fish in the lagoon. He holds some poles, which are sharpened in one end, and which are meant to be driven into the bed of the lagoon. The poles are connected by nets an he’s trying to explain how they are set up in order to trap fish. However, this completely new field for both of us, require more time to get acquainted with.

Having embarked a rowing boat, Raffaele is rowing, while Samuele is standing at the stern, ready to haul up traps, which have been placed on the bottom of the lagoon. It’s nice weather, the water is still and clear, only broken occasionally by the slow and delicate movement of the oars by Raffaele. They want to catch eel, a fish which prefers to move when it’s dark and stormy, according to Giovanni at the Fishermen’s Cooperative of Nora.

Slowly moving forward, we can see various contraptions in the water, that is the poles and nets Carlo showed us, together with some ropes. A trap is lying on the seafloor and Samuele pulls it up, unties the knot closing its end and empties the contents into a bucket. Then, he reties the knot and lets the trap back into the water. They repeat the same procedure 10-15 times, but the catch is small, indeed. Some gobies, a black scorpionfish and a couple of eels only.

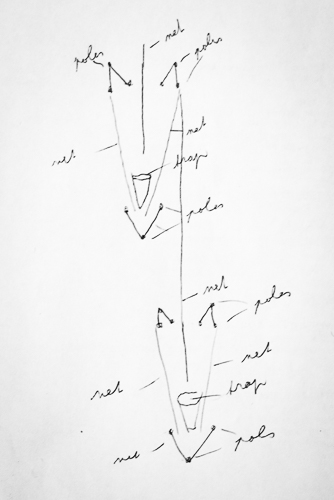

Raffele has been a fisherman for more than 40 years and he kindly makes a sketch of how they set up traps in the lagoon. Firstly, the traps have to be set up perpendicularly to the movement of the fish. Secondly, the traps have to have a large opening, but there have to be obstacles if the fish should try to return. Thus, they set up the contraptions Carlo showed us such that they form two parallel V-shaped nets with a vertical net in between. The Vs form the obstacles for the fish. Having passed the opening, one net is placed obliquely on each side such that it gets gradually more narrow. A trap, consisting of a cylinder-shaped net with a funnel-shaped opening, is placed between the nets. Finally, a V-shaped net is placed behind the trap. This arrangement is repeated in a row extending from near the shoreline to about 200 metres into the lagoon. A coarse sketch is shown below.

Raffaele and Samuele tell us that they fish in the lagoon and the canal from October to March and from April to September in the sea. After having emptied and laid back all the traps, we return to the fishery where the other fishermen are sorting and selling fish, while the local cats are patiently waiting for a morsel.

We also meet Carlo again who explains that, in addition to being a feeding ground for small fry, the lagoon is also used to feed sea water to the salt works at Sant’Antioco. In May, when the fishermen start fishing in the sea, sea water is pumped into the lagoon, pushing large amounts of sea water via a canal to Sant’Antioco.

Finally, we say goodbye to the fishermen, all of them being open and friendly.