I’ve been travelling around the city of Orbetello together with the teachers from the Terramare language school in Orbetello in order to document small-scale food and drink producers in Tuscany and Lazio.

Being accompanied by a local person is invaluable, both because they help me with the language and the special terms used by the people we visit, but also because they spend a lot of time contacting small-scale producers making appointments, driving to where they are located and aiding in asking questions in order to understand more about what they are doing. Besides, although some people speak slowly and clearly, some people don’t, making help with the language mandatory.

Our way of working consisted mostly of one of the teachers from Terramare asking questions and talking with the farmers, while I was busy taking notes in Italian of what they were saying. Afterwards I wrote my notes down on a computer and let the teachers form them into sentences in Italian. Finally, I have translated the texts into English, but not verbatim.

Tuesday 24 March

We visited a nursery called Vivaio Pensalfine located near the coast of the Tyrrhenian sea and Capalbio Calo. This nursery is producing melons, tomatoes, asparagus, squash and aubergine.

Fertilised seeds are bought from Korea, France, the U.S. and Japan. A plastic tray containing a matrix of small holes is used as a home for the seeds, that is, each hole is filled with a mixture of dark turf from the Black Forest in Germany and light turf from Lithuania. Then, an inert material is applied on top of the seed in order to preserve the humidity of the seed in order to assure that the seed germinates. Finally, another layer of the turf mixture is applied on top of the inert material. Next, the trays containing the seeds and the turf are put into a room with high humidity and a controlled temperature always between 25 and 27 degrees centigrade. Then, after some time the seed will grow into a minuscule plant with two leaves. When a third leaf is formed, the incubation period is finished and the next phase can begin. This phase, consisting of taking a part of one plant, making a cut in another plant, putting the stem of the first plant inside the cut of the second plant before applying a spring clip which will enforce a small pressure on the host plant, is called grafting. The purpose is to make the plant being inserted into a host plant more resistant to diseases. We were watching this operation where a watermelon plant was grafted to a pumpkin plant. The roots of the pumpkin has a large resistance to diseases, and the watermelon which is being grafted will inherit this resistance. In fact, the pumpkin plant is also able to accept a melon plant. Another combination is grafting an aubergine plant to a tomato plant. In order to do this operation, a tiny cut in the host plant between its two main leaves is done with a scalpel. Then, the roots of the plant to be grafted are removed before a tiny transversal cut is done to its stem. Finally, the stem is inserted into the cut and a spring clip will apply a light pressure around both the host plant and the grafted one. In this way, the host plant will bring nutrients to the grafted one.

During the growing phase, new leaves on the host plant will often start to grow, but they will have to removed since they will “steal” nutrients from the grafted plant. When the composite plant has grown to a size of about 10-12 centimetres, the spring clips around the host plants are removed, and the plants are sold to other nurseries.

Wednesday 25 March

A farm called Azienda Agricola Biologica “La Selva” located at San Donato, Albinia. La Selva is a farm in which organic agriculture, which has been tried and tested in various ways for about 30 years, is practised.

The cows being raised at the farm are native to Tuscany and are called Chianina because they were traditionally raised in the valley of Chiana. In fact, it is the same race that were used by the Romans, but only for the meat and not for the milk. The calves are born at La Selva and stay with their mothers for 6 months. Then, the animals are separated by a fence, but they are still able to meet each other. In this way, both the cow and the calf will avoid the stress which occur when they are forced to separate soon after birth. It also has a beneficial effect on the quality of the meat, which is sold to restaurants, etc.

Both the cows and the calves live in large sheds consisting of a roof held up by steel columns and they are free to walk around the shed. They eat hay mixed with cereals and vegetables in addition to clover and they are never force-fed in order to obtain a specified weight in the shortest possible time. All the fodder they are eating is strictly organic. At the age of 12 to 18 months, some of the calves are sold for meat. About 25 Chianina cattle live outside all year. They consist of two bulls, about 15 cows and heifers, while the rest are calves. Every 4 years, the bulls are replaced in order to avoid in-breeding since the calves become mature after 4 years.

Appennin sheep are also being raised at La Selva and they are grazing on land which is only being slightly farmed. The Appennin sheep originate from the centre of Italy and is only used for meat. Thus, the lambs are fed by their mothers until they are either sold for meat or they are gradually weaned off drinking milk.

The hay, on which the cows walk, together with the their dung are used to fertilise the fields. In addition, a cycle running for 6-8 years is practised for cultivation of harvests. By using plants the first 3 or 4 years, which provides nutrients to the soil and only using the last 3 or 4 years for growing plants for food, a gradual impoverishment of the soil is avoided. Instead, the succeeding plants get nutrients from the preceding plants left in the soil.

Regarding parasites feeding on the harvests, chemical pesticides are not used. Instead, insects like, for instance, ladybirds, which live in small forests spread around the farm feed on the parasites. The farmland of 450 hectares is divided into various areas for growing fruits, cereals, vegetables and fodder. Almost all the products from La Selva is sold in Italy, while a small part is exported to Germany. Only 10% of the production of fruits and vegetables are sold in their own farmer’s shop.

Friday 27 March

We drove inland in the Maremma towards a farm called Aia della Colonna, which has been run by the Tistarelli family since the early 70s.

The farm is located on the top of a hill and it is surrounded by rolling hills and valleys filled with maquis together with forests. The Tistarelli family has been doing organic farming since 1995 where they are reintroducing and increasing the use of the ancient bovine race called the Maremma cow. This cow has been used at least since the time of the Etruscans as work animals and for their meat.

Fortunately, other farmers have also begun raising Maremma cows for the meat. Until only a few years ago, this cow race was little appreciated because of its large size and also because the race has not been bred for milk, meaning that it will probably not produce as much milk as dairy cows. Instead, the Maremma cow is appreciated for its tasty and meagre meat. An evident characteristic of these animals are their long and wide horns. About 100 cattle are being raised by the Tistarellis consisting of cows, heifers and calves which are dependent on milk. While the cows and the calves can roam more or less freely within a range, the heifers which are ready for selling are collected in enclosed areas where they are being fed hay, clover and fodder grown organically at the farm. In order to move the free-ranging cows and the calves, cowboys (yes, they still exist and they are called butteri in Italy) are used since the cows are very protective of their calves and can easily kill someone with their big horns.

In addition to raising Maremma cattle, a pig race called Cinta Senese, which were originally raised near Siena, is also being raised at the farm. The pigs have a shed, but are free to go outside whenever they wish. Sheep are also being raised and the lambs stay with their mothers till they are weaned off. The wool is not being used due to that it requires too much work. The Tistarellis also raise chickens which are a cross between two ancient breeds of chicken. The hens are free to walk around inside a fence and they also have a shed for laying eggs.

Besides growing fodder for the animals, the Tistarellis are also growing olives and vines. The olives and the vines are only for personal consumption and their guests since they also have rooms for rent. They also have premises for treating the meat from their animals, and the products are sold at their own farmer’s shop.

Production of sausages are done using tried and true methods, that is, they are only using salt to preserve the meat and no preservatives are added. The products are sold to restaurants, wine bars, and so on. The salamis are much appreciated, especially in Tuscany where bread without salt is traditionally being used. The mix between the salted meat and the bread without salt gives a delicious taste. It is recommended to use a red wine called Morellino to accompany this meal. For the modest sum of 15 euros each, we were served a delicious meal consisting of wide selection of their meat products together with bread and wine.

Various types of meat products are sold (the Italian names are included):

- seasoned sausage – la salsiccia stagionata

- a type of salami from Maremma – l’ammazzafegato

- salami – il salame

- chine of pork – l’arista

- bacon – la pancetta

- lard from the pig’s cheek – il guanciale

- ham – il prosciutto

- lard – il lardo.

The products are sold in the vicinity of and in Tuscany.

Monday 30 March 2009

We went to the neighbour of Vivaio Pensalfine called Azienda Agricola Augusto Petroselli, who are producing melons and watermelons in greenhouses and in open fields.

The seedlings which are planted at this enterprise are bought from the Vivaio Pensalfine. Thus, they are buying seedlings which are resistant to disease, more likely that the seedlings will take root, greater growth rate and productivity. The hot and humid climate inside the greenhouses means that planting the seedlings can be started as early as February since no heating is provided to the greenhouses. Instead, heating is provided by the sun. The seedlings adapt well to being planted in the greenhouses and blossom in March. In the blossoming phase, pollination is ensured by means of bees, which live in the same greenhouse1. The female flowers turn into small fruits after having been pollinated, and the melons are ripe in May. Then, the primary harvest and sale of melons are carried out. In March and April, a new batch of seedlings are planted. The first ones are protected by a tunnel2 made of metal bows supporting a “roof” of cellophane which functions as a “house without floor” around them. Before the second ones are planted, a layer of cellophane is laid on the ground . This layer, which serves to hinder evaporation from the soil, has regular holes in it where the new seedlings will be planted. In addition, a tube with minuscule holes occurring at the same distance as the holes in the layer of cellophane is put along the seedlings. The holes let each seedling receive water, drop by drop, which seems to be a very efficient way of artificial irrigation. Thereafter, all the seedlings are covered with some kind of textile held up by metal bows. This “roof” protects the seedlings against diseases and parasites, but it is also porous in order to allow them to breathe. The seedlings which are grown in the tunnels are ready for harvesting in June, while the other ones are ready for harvesting in July/August.

1. The melons inside the greenhouses have male and female flowers and bees are used intentionally, while ants are also doing some pollination. The female flower turns into a fruit after pollination, while the male one, withers away. A beehive is kept inside some of the greenhouses in order to ensure pollination.

2. Inside the tunnel, the temperature can exceed 60 degrees centigrade making it necessary to make small holes at the end of the tunnels. The sizes of the holes are gradually made larger as the seedlings grow larger. This also has the desirable effect of letting insect pollinators enter the tunnel.

Thursday 2 april 2009

We drove from Orbetello, via Manciano and Pitigliano towards Sorano when we arrived at a farm called l’Azienda Agricola Biologica Fonterosa di Piero Bigi.

This family farm is run by Mr. Piero Bigi who wanted to reintroduce traditional cultivation in the early 80s. Now, he is cultivating organically the following legumes:

- Bean – Fagiolo Ciavattone di Sorano

- Kidney bean from Sorano – Fagiolo Borlotto nano di Sorano

- Bean – Fagiolo Cannellino di Sorano

- Name in English??? – Cicerchie di Sorano

- Wrinkled chickpea from Sorano – Cece Rugoso di Sorano and one type of garlic called:

- Red garlic from Maremma – Aglio rosso maremmano

The possibly corresponding names in English have been put in before the original names in Italian in the list above.

Mr. Bigi is aided in searching for new legumes and cultivating them by the University of Siena. Together, they are also controlling the selection of seeds, the various phases of cultivation, and the storing of the new seeds are performed in accordance with the requirements to organic farming. Mr. Bigi told us that during searching for original seeds for the above mentioned legumes, he met a 103 year old woman farmer who was still cultivating wrinkled chickpeas from Sorano. She told him that her grandparents were cultivating the same type of legume. It seems like most of the legumes cultivated by Mr. Bigi originally arrived in Europe about 300 years ago, having been exported somehow from Central Africa. All the legumes together with the garlic cultivated by Mr. Bigi are officially recognised as traditional products from Maremma or Sorano by the Tuscan Commissione Regionale. The farm is located in the area of tuff, a volcanic rock. The tuff originates from volcanic ash and lapilli from the ancient volcanoes of Bolsena and Mezzano in distant geological times.

The abundant content of potassium in the tuff lends the following characteristics to the legumes:

- Absence of a “shell effect” on the outer skin of the legume, produces an effect like it is “melting in the mouth”.

- A rich and intense flavour.

Planting legumes has the beneficial effect that it enriches the soil because they release nitrogen into the soil which also fixes carbon dioxide from the air. When planting, the legumes are planted on pieces of ground which are far from each other, in order to avoid pollination which could have caused hybridisation. No fertilisers, no insecticides and no weed-killers are applied during cultivation of any of the products. Collection of the finished products are done manually. All of the above mentioned legumes are fundamental ingredients of the courses in the Mediterranean diet and the Tuscan kitchen.

Friday 3 april 2009

We drove just a few kilometres from Orbetello in order to reach a place called San Donato where a farm called Azienda Biologica e Agriturismo Rustici is located.

We were showed around by Giuseppe Rustici, who runs the farm in cooperation with his father, his brother and their wives. Besides, they employ 8 people. Originally, the whole area around the farm was marshland, but it was reclaimed by draining during the 1950s.

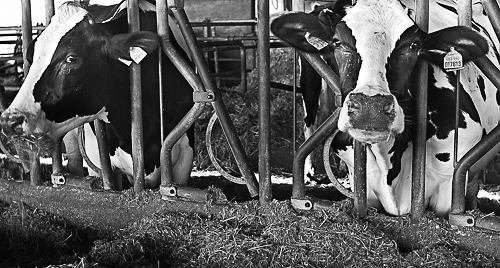

In addition, the land which was formerly owned by absent landowners were divided up and given to independent peasants. Now, 60 years later, the farm has about 100 Frisone dairy cows which are only meant for milk production. In addition, they are raising Maremma cows in an enclosed space and a mix between Limousine-Chianina which live in another enclosure nearby. While the dairy cows live inside a shed, but where they are free to walk outside, are inseminated artificially at regular intervals (60 days after having given birth, i.e. annually), the cows living outside are inseminated by bulls.

The farm has two Maremma bulls and one mixed race for this purpose. The Rustici brothers together with their father have decided to run the farm as an enterprise run in an organic way. This means first of all to let nature run its course and not to push things, e.g., the time between the birth of a calf and another insemination of a dairy cow is extended from the minimum one month period to two months. Besides, cultivation of the harvests and treatment of soil are done organically, the animals are treated as well as possible, new and genuine products are continually developed and brought to market. The Rustici family has been trying for several years to promote the sale and the consumption of raw milk. Raw milk is the milk which has been milked from the dairy cows and not treated in any way, except filtration and refrigeration at 4°C.

This leads to several properties which are highly appreciated by their customers:

- raw milk is easily digestible, containing enzymes in an active form and aiding in improving intolerance to drinking milk.

- raw milk aids in absorption of calcium because it conserves phosphates. Instead, heat-treating the milk will prevent this property.

- raw milk contains large amounts of unsaturated fats which are fundamental for the human body, gives energy to the body, aids in eliminating toxins and maintains the elasticity of the veins.

Among the initiatives of the Rusticis for taking care of the environment is to extend their organic cultivation to neighbouring farms.

The advantages are twofold:

- restore the original organic components by preventing all use of pesticides, weed-killers and other chemicals.

- provide fodder, cereals and legumes necessary for the nutrition of their animals.

The Rustici farm has been officially recognised by a regional corporation called ARSIA and has received a certificate of conformity guarding the rules of running farms organically. The certificate has to be renewed at regular intervals. The health of the dairy cows is closely monitored. Each cow is furnished with a pedometer which monitors their movement, while the amount of milk each cow produces is also recorded as a means of detecting health problems at an early stage.

The calves are separated from their mothers immediately after birth, but the calf is completely dependent on drinking the milk of its mother for the first 10 days of its life. Thereafter, it is fed milk from the other dairy cows for another 80 days. Thereafter, the calves are placed together in enclosures where they are free to be inside a shed or walk outside on a meadow. As the calves turn into heifers, they are placed in another enclosure until finally “advancing” to be dairy cows at which time they will join the other ones.

The raising of cows outside (about 50 Maremma cows and about 70 mixed race cows only meant for meat production) take place about 25 kilometres from the Rustici farm near a town called Magliano about 150-200 metres above sea level. They live in a beautiful area consisting of hills and valleys covered with maquis and with a view of the sea. Ancient fountains nearby are used to provide water to the animals.

In summer, the Maremma cows, which grow slowly, needing large open spaces and being able to move long distances, are moved to other meadows nearby where they are able to live off the land, whereas they are fed by the farmers in winter. Among the agricultural rotation techniques reintroduced by the Rustici brothers which is beneficial for the soil is called green manure. By means of this method, one type of plant is used to prepare the soil for multi-year plants the next season.

A suitable plant for this purpose is called favino in Italian and probably mangetout in English, a legume which makes it possible to obtain the following main objectives:

- after having spread dung from the cowsheds, the legume called mangetout, which collects nutrients from the dung, is seeded in the same place. Thus, when growing, it will transform the dung into elements which will enrich the soil after the plants have died.

- the mangetout prevents other plants from growing up in the same area in which it is growing.

- after the mangetouts have died, they are left on the field, thus providing a natural weed-killer.

Besides, all legumes enrich the soil with nitrogen. Before a new cultivation is applied, the plant residues are mixed mechanically providing nutrients or green manure to the new cultivation.

The Rustici family has lots of ideas for expansion of their farm, not limited to extending their land or raising more animals, but also to receive tourists. In fact, around the meadows used by the cows, numerous paths are situated which are suitable for both hiking and mountain biking and they are ready to accommodate groups, who want to spend their holidays in the countryside. They also serve food based on their own locally grown and raised food together with their un-pasteurised or raw milk.

Monday 6 april 2009

We drove from Orbetello through Manciano and just before reaching Pitigliano, we turned right towards Farnese. Just a few hundred metres afterwards, we reached the farm called Azienda Agricola Belvedere situated on top a hill.

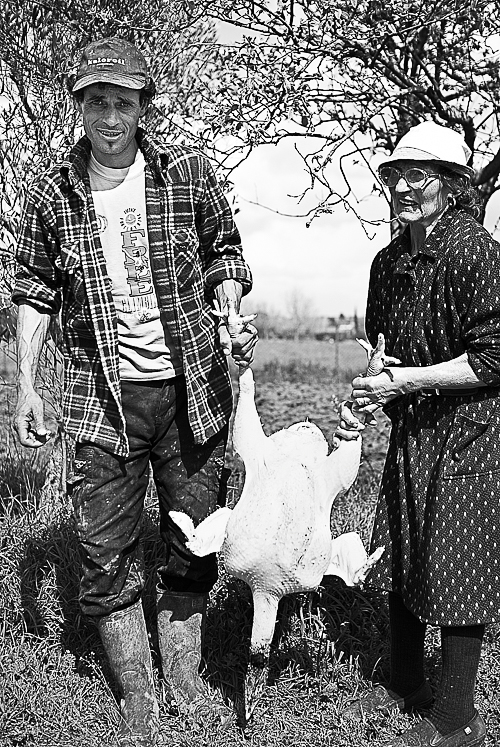

One of the first sights which met us on arrival was Giancarlo’s, the owner of the farm, 75 year old mother slaughtering a turkey. Later, we were also watching her slaughtering a hen and a rabbit. A very unusual sight, indeed, for a city guy like me! However, the other free-ranging chickens seemed not to notice at all or just showing utmost indifference that two of their brethren had just been finished off!

The Belvedere farm being situated between the Tuscan commune Pitigliano and the Lazian commune Farnese, resides on very fertile soil although it is outside the zone of tuff. All the countryside around the Belvedere farm was owned by large landowners up until the 1950s when an agricultural reform abrogated this custom and gave the land to the peasants. Giancarlo’s mother could still remember her grandparents had the right to stay in the farmhouse, but having to give half of whatever they produced to the landowner. After the agricultural reform, the family of Giancarlo has extended the area of the farm to 150 hectares by buying up land and by inheritance.

The principal plants which are cultivated at this farm are olives and grape-vines. The vines are mainly Sangiovese, Cabernet and Rosso di Sorano where most of production is sold to wine-merchant called Cantina Sociale. However, the pride of Giancarlo is the wine cellar, dating from the 1400s and facing north to avoid the sun, which has been excavated below the family’s house. We were invited to taste his Rosso di Sorano which had an excellent taste.

Regarding the olives, Giancarlo cultivates three types of olive trees, Cannino, Leccino and Frantoio, which have some of the following general characteristics:

- Cannino olive oil: tasty, pungent, forever young and can be conserved a long time.

- Leccino: the Leccino trees are robust and not susceptible to cold spells. The olives are big and meaty, while the oil is light and delicate, but not suitable for long conservation. May be harvested in October-November.

- Frantoio: not able to produce olives if the tree is subjected to low temperatures, but it produces an excellent oil which is aromatic and fragrant.

The following animals are raised at Belvedere:

- Milk-producing Frisone cows and meat-producing Limousine cows.

- Meat-producing Cinta Senese pigs whose meat is sold both as fresh and as sausages, salamies, ham, lard, etc.

- Meat-producing Appennin sheep.

In order to enrich the soil, dung is used, while no chemicals are added. The Belvedere farm has not been recognised as an organic farm due to too much bureaucracy. We were also shown a field of rapeseed which was only used for fodder for their animals and not for making vegetable oil.