We were passing through the village of Suseni, looking for a specific house number when we found it. It looked like an ordinary brick house with a fence along the road. It certainly didn’t look like a farm at all from the road. We entered the property and an elderly man showed us where we could find the owner of the farm, Mr Bányász József.

He invited us inside the kitchen where he served us cheese and coffee. Before, he called himself an artificial farmer because he was only talking about agriculture, trying to convince everyone to be a farmer. He was told to stop talking and start working himself as one. He spent 5 years convincing himself that he could be a farmer and now he’s a full-time farmer. 5 years ago, he was a director of an association, he quit, people told him he was stupid and he lost prestige because people prefer money to a lowly life as a farmer. Anyway, after 5 years as a farmer, he thinks it’s a good life.

He calls the farm The milk mine because he’s mining the farmer’s life, trying to show others how farmers who treat their animals and their land well are working.

Mr Bányász is a thinking farmer and here are his statements:

His main objective is to live as his great-grandparents would have lived if they were living now.

He’s trying to live as closely as possible to nature.

He and his family are not reinventing things, and they try to conserve as much as they can.

He considers the domestic animals as partners, not just subjects. If they are ill, he feels ill too. He tries to understand them, how they are thinking, always trying to help them. He wants others to think of animals like he does. He emphasizes that the domestic animals ARE his partners.

Unfortunately, most farmers look at domestic animals as a way to make money and not as partners. You don’t just keep animals, you also need to know all aspects of animal husbandry.

He says you can’t buy life quality.

He’s not looking for profit, just to have enough to survive.

He’s getting inspiration from traditions.

His way of thinking is different from the other family members.

He says art is pain and a farmer’s life is hard.

He considers art, dance, folklore as a higher form of hardship. For outsiders, folk dance is just dance, but the performers give out pain through dance.

He’s making “simple” cheese, and he would like to know more about milk chemistry, bacteria etc. He would study more if he were young.

He doesn’t go to markets, you must come to him and talk to him, if he likes you, he will sell you cheese, if not, he won’t. He has a stable customer base. He gets emails from Bucharest from people who want to buy his cheese. He replies that they have to come here and talk to him first.

His mission is to tell everybody what needs to be done.

He’s talking sincerely about living in harmony with nature.

He thinks nature doesn’t have enough resources and we need to consume less.

The whole family is trying to be independent, producing as much as possible for themselves like vegetables, fruits, bread, milk and cheese.

He’s bartering cheese for vegetable oil, sugar, salt, etc.

He’s eating meat from animals, he hasn’t resolved yet how to treat them as partners and eating them, it’s a compromise.

He doesn’t want to be a vegetarian, but he’s reflecting on it. Pigs, chickens, hens and turkeys have been slaughtered here. Male cattle have been sent to the slaughterhouse, but never dairy cows. He sells male calves to others, which is not a solution. Instead, he leaves the problem to others.

Dairy cows live their natural life and are buried here.

He doesn’t like the agricultural system in Romania, but he doesn’t work against it.

After having presented his thoughts and opinions, he invited us to have a look at the farm.

This farm has an extension of 15 hectares.

There are 3 generations living in the same house and all the family members are working on the farm except his son. He will graduate as an agricultural engineer soon, but he doesn’t want to run the farm as his father. He needs more money, but maybe he will change his mind with time.

They have good quality livestock and they have 9 cows of which 5 are milked. The cows produce 180-200 litres of milk per day, giving about 10 kg of cheese.

We went inside a barn where there was the milking place for the cows. While the cows are eating from a trough, a chain is placed above their necks. Next, they are milked by a machine and the milk is pumped to the dairy adjacent to the milking place.

During our visit, calves were eating freely from the trough, while a one week old calf was living in a separate place.

The cows are inside at night, lying on hay next to the milking place.

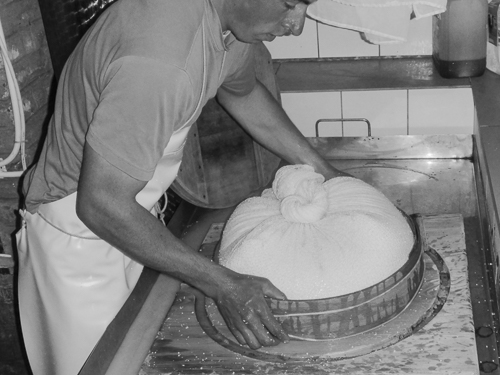

Next, we went to the dairy where a worker called Tamás was making cheese. In fact, he was pulling a mass of curds out of a copper tank by means of a porous cloth, then he put it in a wooden mould.

We were also shown the cool storeroom where the cheeses marked with the date of production were maturing on wooden shelves. In addition, there was a saltwater bath for the small cheeses. By letting them stay in brine, the salt kills bacteria, adds taste to the cheese and aids in expelling whey.

Next, we went down towards the meadow below the houses. We passed a big wooden structure, which had been designed by students at a local university and built by local people, but it was still missing roof and walls. It would be turned into a community hall next year.

There were some hay cylinders inside the wooden structure, but Mr Bányász said they are expensive. His father-in-law prefers haystacks, which they can make themselves. Actually, we passed two big haystacks on our way to the meadow.

The meadow which belonged to this farm were surrounded by other meadows, while we could see the village in the distance. Scattered trees were growing and the daughter of Mr Bányász followed us, telling my guide that there was ground water below the meadow for both the trees and the cows.

She works very hard, she has studied photography and likes applied arts, she wants to go abroad and have time for herself and she wants to study more. Her brother wants to work here with workers and modern machines.

When we went out on the meadow, we passed one cow which was alone. Going further, we met the rest of the cows, which apparently liked to stay together.

There is a hierarchy among the cows, they are pushing each other, even using their horns. One cow was dehorned because she was hurting the other ones. One cow had scars because she wanted to advance in the hierarchy, but didn’t succeed.

The cows had been born on this meadow, they could be outside all year if they wanted to, but they could also go inside if they preferred and they were milked in the morning and the evening.

The cows are made pregnant with artificial insemination. There is a catalogue with bulls and Mr Bányász selects the bull which is most suited to each cow.

On our way back to the house, we passed a yard with poultry and a turkey, a very common sight in Transilvania.