Økologisk Buskerud recently arranged a visit to Økologisk spesialkorn in Sigdal in order to have a look at their flour mill. In fact, this was a very good way of complementing a visit to the same area almost 2 years before and documented here.

Being in late April, the farmers hadn’t even started seeding their fields, but the flour mill and the adjacent flour shop was open. Unfortunately, the flour mill wasn’t operating, but this was as expected since it’s used in autumn when the grain harvest has finished.

Obviously, bread has been a part of our diet for thousands of years and this article shows that people in the Middle East were making flour 14,000 years ago.

In addition, research has shown that life was incredibly hard and that women could spend 5 hours grinding grain daily.

From then to now, turning grain into flour has changed from a strenuous task to something done by machines driven by wind or water, but nowadays mostly by electricity and which very few people know anything about.

The company, Økologisk spesialkorn, have their own flour mill and it’s the first company in Norway, which is approved for producing, storing and selling seeds of more or less rare types of grain like emmer, einkorn, spelt, Nordic rye called svedjerug, Dala wheat (a type of wheat which has been selected by farmers for generations), a Norwegian barley called Domen and naked barley (that is, barley without hull) called Pirona.

Our guides were Anders Næss, organic farmer and former managing director of Økologisk spesialkorn, and the farmer Guttorm Tovsrud on whose land the field trial was done.

The mill was originally built by local farmers in Sigdal as a cooperative and it received grain from local farmers for many years until it was closed down. However, Økologisk spesialkorn bought it, restored the building and bought a new flour mill some years ago.

As we were told by Terje Nesje at Holli mill, there is no education for millers in Norway and Anders went to the Danish company Aurion, which is using Austrian stone flour mills, in order to learn about milling. In fact, there is an active association for millers and those who are interested in milling in Denmark.

Having entered the mill, it was obviously a building which had been made for a specific purpose although it was quite difficult to understand what at a first sight. Everything was made of wood, stairs led upwards and downwards and some machines were standing in various places. First, Anders led us to the base of the building where the flour mill had been installed. A machine with a diameter of, say, one metre, and a height of, say, one and a half metre, was the flour mill, while just above it was a tube and an open box full of grain. When the flour mill is in operation, grain from a silo is fed through this tube into the mill.

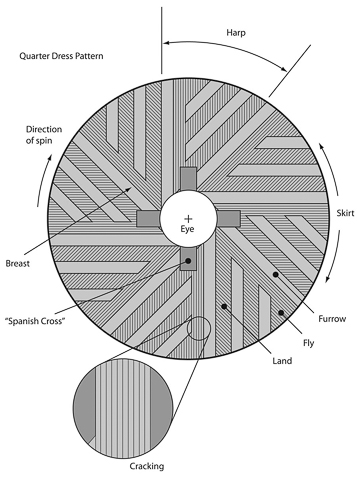

The millstones were inside the flour mill and they were not visible. As explained here: millstones come in pairs. The base or bedstone is stationary. Above the bedstone is the turning runner stone which actually does the grinding. The runner stone spins above the stationary bedstone creating the “scissoring” or grinding action of the stones. A runner stone is generally slightly concave, while the bedstone is slightly convex. This helps to channel the ground flour to the outer edges of the stones where it can be gathered up.

An animation of how scissoring works and a glossary of mill terms are included. A typical millstone is shown below.

By Stevegray at the English language Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=728078

Just like at Holli mill, the miller at this mill also has to use hearing and sense of smell in order to get the flour as wanted. It is possible for the miller to get samples of flour during milling such that it can be felt, touched and even tasted. Lastly, the miller can monitor the current consumption of the mill. Then, by using all 5 senses, the miller can vary the distance between the millstones by means of a handle on the mill. In this way, the miller can ensure that the temperature is less than 40°C avoiding excess heat during milling.

At the base of the flour mill there was an electric motor and a tube through which the motor would force the flour upwards to the top of the mill. From there, it would fall down into a sieve with various openings such that the miller could vary the size of the particles and get a specific flour.

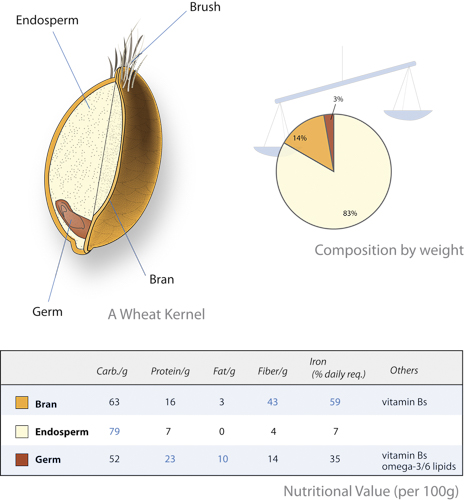

Anders told us that their customers didn’t like their flour in the beginning, because it was beige due to bran, and not white as it should be. The following picture shows a wheat kernel, but other types of grain look similar.

By Wheat-kernel_nutrition.svg: Jkwchuiderivative work: Jon C (talk) – Wheat-kernel_nutrition.svg, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12889006

This flour mill is not heated, leading to fewer problems with animals and insects trying to eat or contaminate the flour, which is a real problem in warmer countries. The only room, which is heated, is the packing room where a certain amount of flour is let into paper bags, which are put into cardboard boxes, ready to be shipped to customers.

Last but not least, this company doesn’t mix grain in any way such that there is full traceability from each farmer, field and time of harvest.

Having finished our visit in the mill, we were invited to eat freshly made pizza. Økologisk spesialkorn has a mobile, wood-fired oven and the present managing director, Rune Menninen, was busy tending the oven and folding pieces of dough, which consisted of a mixture of emmer and spelt and had been made the day before. He flattened pieces of dough manually, put on tomato sauce, pepperoni and cheese and put it in the oven. A few minutes later, he took it out again, having made a freshly made pizza. Since there were so many visitors, about 25 in all, he had a lot to do.

I also met Guttom Tovsrud, a farmer who was owning and running the field trial described in Field trial of growing cereals.

He had been doing organic farming for 15 years, and when he started, the farmers doing conventional farming thought he would get ever smaller harvests and more weeds. Instead, it was the opposite which happened, mainly because organic matter, in particular carbon, in their fields is decreasing according to Anders Næss.

Mr Tovsrud also told us that after having grown spelt 4-5 years on the same field he practised crop rotation, replacing the spelt with clover, which will add nitrogen to the soil, an essential nutrient for plants.

During 2018 when there was a drought in Norway, he lost very little of his spelt harvest. He attributed this to the the deep roots of the spelt and the porous structure of the soil due to an abundant micro-life in the soil. In addition, spelt has a long stem, placing it farther above ground and making it more difficult for parasites to reach the grains. Interestingly, this is the same advice I got from a wine farmer in Italy. That is, he wanted to keep the canes of the grapevines at least 50 cm above ground in order to avoid parasites from the ground.

Spelt has a hard hull, which has to be removed before milling. The hard hull also leads to that spelt has to be dried slowly, else only the hull will dry, while the endosperm remains humid.

It was a great pleasure to visit somebody who work so hard to make high quality products for consumers.