We arrived at the farm of the Muñoa family before sunrise. Inside a big building, we could see lots of sheep being milked by milking machines operated by Javier Muñoa and his brother-in-law. His former assistant has recently retired and he’s looking for a replacement, but he hasn’t found a suitable person yet.

Each time a group of sheep had been milked, they were let out through an exit, while another one was allowed to enter through an entrance. All in all, 270 sheep of the Latxa race were milked this morning. Latxa sheep are considered to be native to the Basque region, but genetic analyses have traced them to present-day Israel from where they started migrating about 7000 years ago. They are very well adapted to the mild and wet climate of the north of the Basque Country.

Having finished milking, we followed Javier to the farmhouse dairy, where the milk from the sheep already had been pumped into an open vessel, which obviously was part of a cheesemaking machine. Small dairies light a gas fire below the vessel containing milk in order to heat it, but Javier just turned on a switch to heat the milk to 38°C. Then, he prepared rennet, a substance which is used to start curdling, by mixing solid and liquid parts by means of a kitchen mixer, then pouring it into the milk. Afterwards, he started stirring the milk by inserting a couple of harps, a metal structure with parallel metal wires, into a part of the machine and turning on another switch. After some time, he stopped the stirring, letting the milk slowly turn into curd.

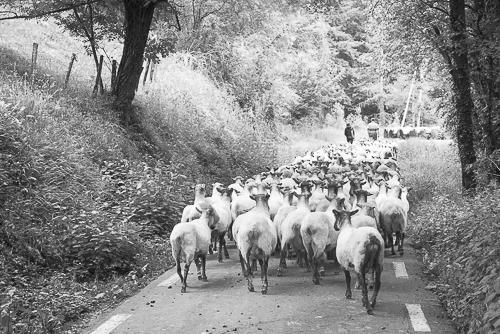

While the milk was turning into curd, Javier went to another barn where he filled feed in a trough, then he let young sheep about 6 months old enter in order to eat. Having eaten, they were led back to the other barn. Then, he released a large flock of sheep, walking in front of them on the road down to a communal meadow where they were allowed to graze freely. Next, he released another group of sheep on a pasture on his own property.

We returned to the farmhouse dairy where the milk had curdled and it was time to separate liquid and solid parts, that is whey and cheese. First, Javier restarted the machine, letting the harp stir the curd. Having stirred the solid stuff into small clumps, he exchanged the harp with another metal tool, then letting the machine continue stirring until the mixture looked homogeneous. Next, he put a perforated plate into the liquid on one side of the vessel, likewise on the other one. While one of them was stationary, he started pressing the other one against the first one such that the whey was allowed to exit through the holes in the plates, leaving even more cheese mass inside. After having compressed it as much as possible, Javier used a stencil to divide the cheese mass into cubes whose side was 10-15 cm. Having already put porous cloths into a lot of plastic cylinders, he lifted the cheese cubes and put them one by one in the cylinders. Next, he put small labels on the top of each cheese in order to ensure traceability. Finally, he put lids on all of them and put them in a rack were they were subjected to continuous pressure in order to press out as much whey as possible.

Having finished the cheesemaking, Javier showed us a brochure from the Guild of Fine Food where one his cheeses had been deemed to be among the 50 best products worldwide in 2015. In addition, it also got an award of three stars, where one star means delicious, two stars mean outstanding and three stars mean exquisite. This is even more impressive when there were more than 10,000 products which were entered into the competition.

The cheeses made at this farm from part of Idiazabal cheese and it is a Denomination of Origin, meaning it has to be produced in the Basque region from the milk of Latxa or Carranzana sheep and the cheese has to be prepared in certain ways. There are about 112 cheese producers, who make Idiazabal cheese and they are located in the territories of Araba, Gipuzkoa, Navarre and Biscay.

Although Idiazabal cheese has existed for many years, it was common for sheep farmers to send sheep’s milk to dairies where it was turned into cheese. About 30 years ago, there was a marked change when a priest called P Mitxel Lekuona, persuaded farmers to make cheese themselves because the price of milk was steadily decreasing, giving the farmers very little profit. He encouraged them to turn all the milk they produced into cheese and to improve their way of making cheese. He ran courses in cheesemaking, bought various tools and organised excursions to other cheese producers, e.g. in France.

Regarding the sheep, the ewes are made pregnant by means of artificial insemination, but if it doesn’t work, Javier let the ewes stay with rams for some time. Lambs are born at the end of November and some of them are slaughtered at Christmas when the farmers get the highest price for them. When the lambs are weaned, milking of the sheep is started. Ewes, which aren’t able to get pregnant are sold to Greece and Lebanon.

Although many sheep farmers bring their sheep to the highlands in summer and to the lowlands in winter, Javier Muñoa lets them stay at or near his far all year.